Especially for Ours (EfO) is a new blog series. The title is taken from a W.E.B Du Bois’s quote about The Brownies’ Book, a magazine created for African American children during the Harlem Renaissance. Du Bois expressed that The Brownies’ Book was “for all children, but especially for ours.” We believe that the Black book creators spotlighted in EfO share that sentiment about their stories and art. EfO will feature a brief book review and an interview with the author or illustrator.

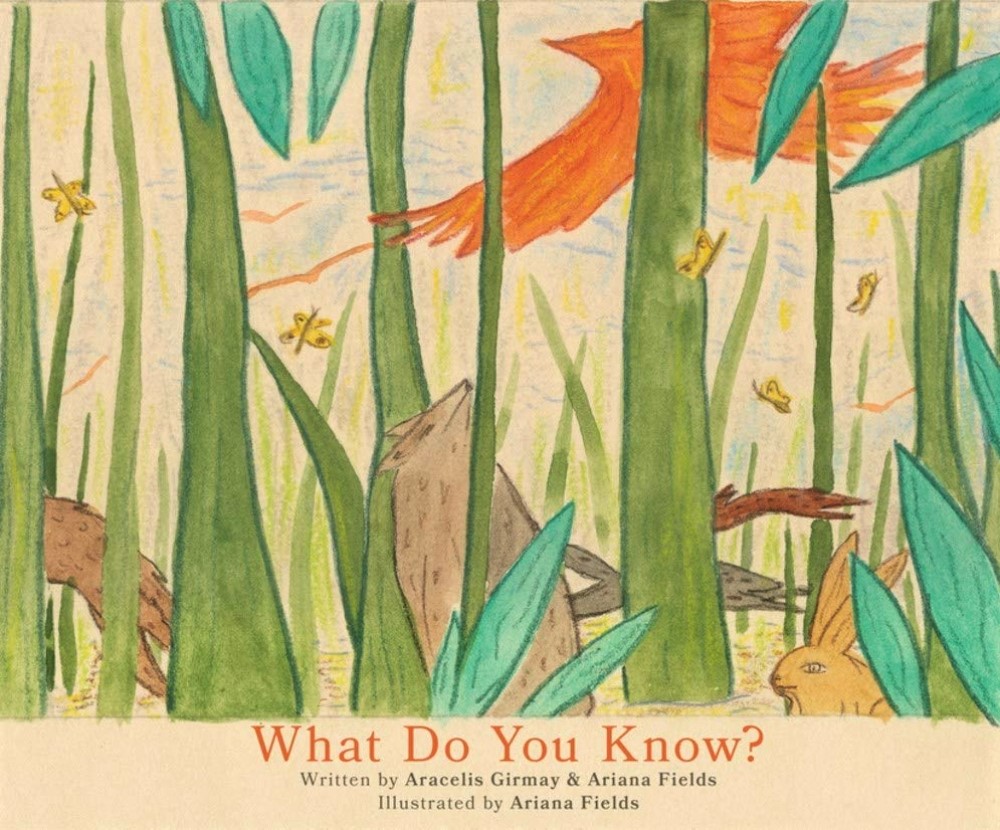

Poets and sisters Aracelis Girmay and Ariana Fields collaborated on the picture book What Do You Know? Girmay is the author of three books of poems and the editor of How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton. Her debut children’s book, Changing, Changing: Story and Collages was released in 2005 (George Braziller). WDYK? is Fields’ debut as an author and illustrator.

Review of WDYK?

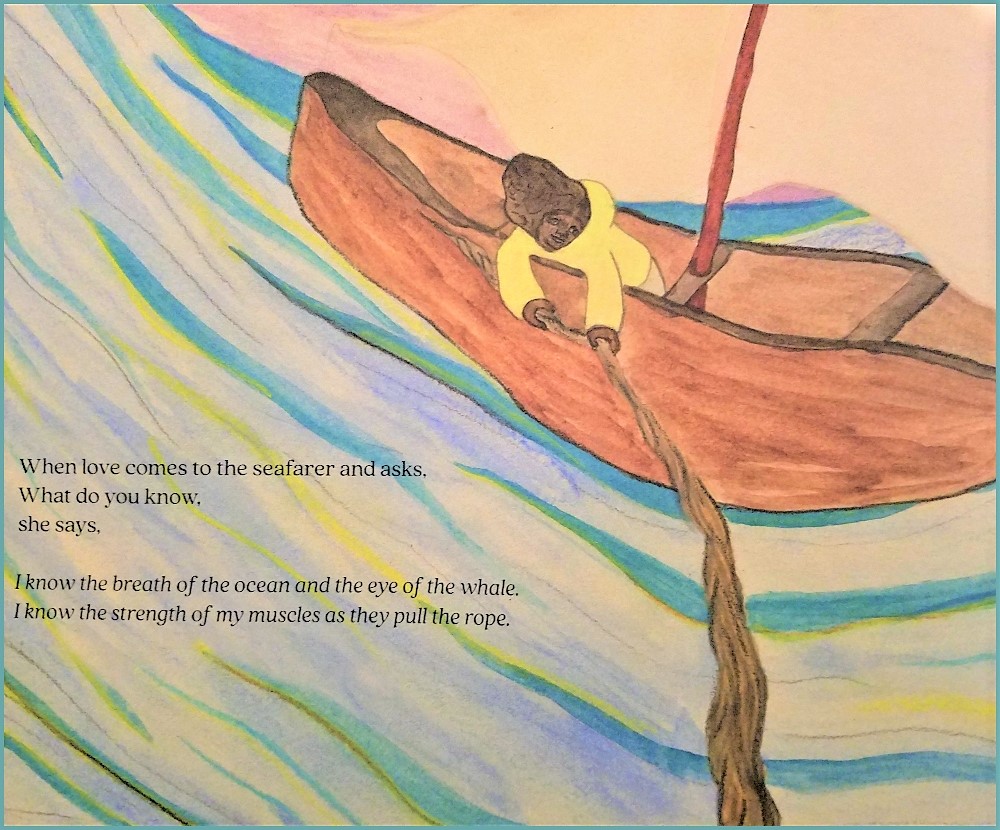

The title of the book and “When love comes,” a recurring line in the poem, pay homage to Sharon Olds’ “Looking at Them Asleep.” WDYK? forces one to think. Or maybe force is not the right term as it can suggest aggressiveness, something this poem, or love, is not. For it is love who asks “What do you know” in serene dialogues with its many subjects (ash from a volcano, a rock, farmers, fruit bats, etc.). The subjects magnificently radiate the confidence that comes with knowing. For example, the seafarer says, “I know the breath of the ocean and the eye of the whale…And I know that star and that star.” The forest knows colors and sounds and smells. The historian knows stories. The land knows joy, laughter, and the hopes of the ancestors. The humbleness and simplicity of Fields’ watercolor illustrations embody the pensive nature of the poem—a poem that gently nudges us to explore beauty, courage, truth, hope, and regard—of and in self, others, our world, the earth, and space—so that when love comes to us, we too will know. The ancestors are pleased with the sisters’ lyrical offering.

Interview with Aracelis Girmay (ag) and Ariana Fields (af)

—Can you introduce yourself and tell us about your early interests and experiences with writing and art?

af: Hello. My name is Ariana Fields, co-author and illustrator of What Do You Know? My interest in art started at a very young age. I grew up with art all around the house. I studied at the San Francisco Art Institute with a focus on printmaking. It’s funny; I remember in one of my art history classes looking around and noticing I wasn’t the only one who filled their notes with sketch drawings in between writing. At that point, I really felt like, “Wow, I found my people.”

When I was in art school, the power of storytelling through image and text became even more clear to me. We are surrounded by image and text storytelling every day, but it wasn’t until I studied printmaking that I really started to understand the emotion and power that image and text can really carry. When I later studied landscape architecture, it felt like I had come full circle. I began to recognize the story we all print in this world and the impact those stories can have far beyond the lifeform or object that made it. I continue to be especially interested in the stories within the land, whether they be torn roots in dirt, skateboard marks on concrete, or a snail’s trail. It’s difficult for me not to wonder about the journeys and occurrences of those specific marks.

ag: And I’m Aracelis Girmay, Ariana’s sister and co-author of What Do You Know? I’m a mother, poet, and teacher. I love what you say, Ariana, about the stories within the land. I think we overlap deeply in that way. When I was little, I could play in the dirt for so long, observing and wanting to understand. I remember Ariana doing the same when she was little. I think my connection to writing is informed, actually, by that same childhood impulse—which, for me, had to do with diaspora and having big questions about home, place, loss, and ancestry. I have always been interested in the histories of places and people. How did we come to be here? Who and what was here before us? What were their ways of being here? Probably those questions were some of the very questions that compelled me to major in Documentary Studies with a focus on long-form nonfiction and oral history when I was in college.

First and foremost, I came to writing as a reader. I was profoundly moved and stirred by the ways that writers like Lucille Clifton, Toni Morrison, Kate Rushin, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez told, kept, and were influenced by the stories and histories of their people and their imaginative strategies for survival.

—Writing is mostly a solitary craft. What was your collaborative relationship like as sisters and as co-authors? And is WDYK? your first project together?

ag: I’d say Ariana and I have been making things together (informally and as friends and siblings often do) since she was little. We’re 11 years apart, so I was lucky to witness the roots of her play and observations, and we have such a familiarity with one another’s imaginations. We’ve made a lot of things together as a way of just being around each other, but nothing formal. This is the first thing we made and stayed with and thought to share with others. This book and our hope to share it with an audience added new dimensions to our dynamic as sisters.

We had to learn to revise together, to figure out a way to work across different aesthetic sensibilities and work rhythms, to make a braid of our expressivity. Compared to Ariana, I’m much more assertive and quick to make decisions, so I really struggled to find a way to communicate clearly with my sister while also trying to be aware of how much space I take up for her.

af: For me, making art has always felt more solitary. Drawing in solitude came naturally. When I wasn’t outside playing, I would often make things by myself. I think this is also more natural for me because of the age gap between my brother and sister. Because my art practice is more solitary, this collaboration with Aracelis and Enchanted Lion definitely pushed me far out of my comfort zone. I had to confront my shyness, insecurities, discomfort in communicating an idea, and my habit of solitude. This collaboration was a true teacher for me and really opened up new pathways of growth.

—This line from the author’s note, “We wrote the text together, Ariana made some drawings, and then we put it aside, as though planting a yam into the earth, allowing it its quiet and growth and sleep. Two years later. We unearthed it to see what it might be,” is incredible. How pleased were you with what you unearthed, or did you make any changes before sending it to Enchanted Lion Books?

af: Thank you so much. As the manuscript formed, we began to feel like we were holding something very special that we hoped to share with others. We made slight changes before sending it to Enchanted Lion.

ag: Yes. And then, a host of new revisions came once Ariana began working on the illustrations. That work put new pressure on the language and pushed us to ask new questions about pace, order, and intention. Once the book really came together, and most of the illustrations were done, we had several deeply thoughtful conversations with our really genius publisher, Claudia Zoe Bedrick. We thought again about pace, sound, order, and where language could be swept clean or sparer because the image was already doing so much.

—Ariana, how did you decide to approach the illustrations? Were images coming to you as you were writing the poem, or did you sit with the words for a while?

af: Images were flowing through my mind as we were writing the text, but of course, things changed once all of the words were there. I really wanted the images to be able to complement the text but also have an element that could suggest even more stories or possibilities that can’t be told by a human voice. I also wanted the elements to feel hopeful and to carry something even more than human. What do we know? There is so much that we don’t know, and the Mystery is what I wanted to honor. My hope was to create visuals that would allow the viewers to imagine what else could be. I wanted to make images that would hold space for readers’ imaginations to run wild, to feel the excitement of exploration but to also be aware, kind, and respectful within that exploration.

A huge part of my process was being outside and quietly observing what was happening all around me while reading lines from the book. A lot of the visual inspiration came from a rhythm I felt when looking and digging through dirt or staring at trees and being aware of the activity that takes place in them. I was inspired by the spring when things come out of dormancy and are born with instincts that will form into the knowledge of what it is to live and survive here in this life on and in this earth, ocean, and sky.

—It is sometimes difficult to explain poetry to children. How do you introduce poetry to children?

ag: I believe young people engage with the world as poets. Their coming to language, their play with sounds, their attention to the world—it is poetry. That said, I think there are so many ways to encounter a poem. You can let the sound wash over you without trying to pin meaning down. You can pay attention to what it makes you feel and think and wonder. You can pay attention to the questions it makes you ask of it or yourself or the world. I’ve had the great gift of getting to work as a poet in schools with young people from kindergarten to middle school and then students in high school and college. I’ve always asked students to read the poems out loud or to listen as someone reads the poem out loud. And then, we observe (no observation is too small!).

We talk about how the poem makes us feel, what we notice, what we wonder. And we always write in response to what we’re reading—group poems with the really little ones, where I take notes, and we add details and take away details just to see what happens…kind of marveling at revision and change and how a sentence or phrase can be like an accordion stretched wide and then pushed back into a small shape again. Young people are so game and ready to play, and this, to me, is an essential part of poetry and how I think of talking about poems with children.

Please return to this space on Tuesday, July 27th, for Part II of the interview. Aracelis and Ariana speak to educators about the themes in WDYK? and share their hopes for young Black readers.

What Do You Know?

Aracelis Girmay | Ariana Fields | Enchanted Lion Books | August 17, 2021 | PB | 56 Pages | Amazon | Bookshop | IndieBound

Connect with Aracelis Girmay on Twitter

Connect with Ariana Fields on Instagram

If you believe BCBA provides a valuable service, please take a few minutes to donate and support our mission to promote awareness of children’s and young adult literature by Black authors.

Amazon/Bookshop/IndieBound Disclosure: BCBA is a participant in the Amazon, Bookshop, and IndieBound Affiliate Programs. The affiliate programs offer participants the opportunity to earn fees by linking to Amazon, Bookshop, and IndieBound websites. Clicking on the book links will direct you away from this site. Thanks for your support!